ESSANAY STUDIOS 1333-45 W. Argyle St. (1908-15; various architects) ESSANAY STUDIOS is the most important structure connected to Chicago’s role in the early history of motion pictures. Essanay was one of the nation’s premier movie companies, producing hundreds of motion pictures, featuring such stars as Charlie Chaplin, Gloria Swanson, and cinema’s first cowboy hero — and a co-founder of Essanay — G. M. “Broncho Billy” Anderson. After its founding, the company also began making movies in California, where reliable weather facilitated outdoor filming. Changes in the movie industry, the defection of Chaplin as the company’s star performer, and disputes between Anderson and his co-founder led to the collapse of the company in 1917. The fanciful terra-cotta Indian head at the building’s entrance was Essanay’s logo. Significant Features: The designation specifies “all exterior elevations, including the roofs, and the structural systems of the buildings.

Essanay Movie Studio1333-45 West ArgyleAvenue Chicago, Illinois Erected: 1908 (with additions through 1915)

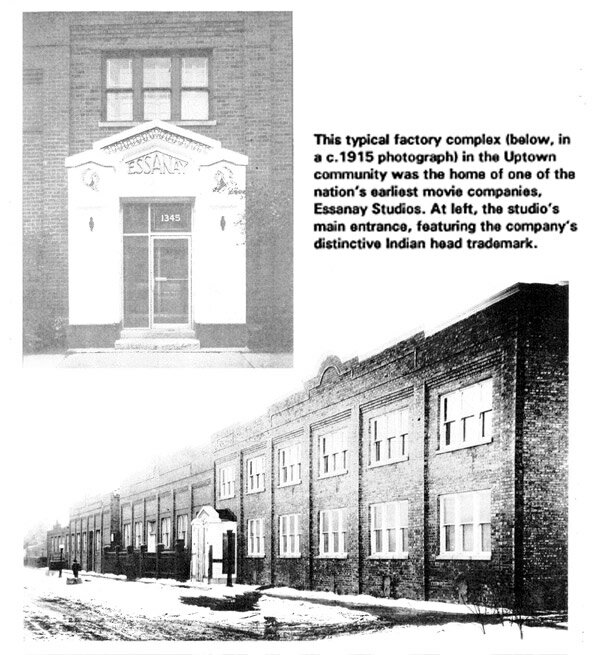

Behind the walls of what at first glance appears to be just another old factory complex in the 1300—block of West Argyle Avenue, movie executives George Spoor and Gilbert Anderson created the celluloid dreams that filled movie houses throughout the nation in the early part of the century. Only the fanciful terra~cotta entry with its Indian head design suggests the distinction of its original occupant. the Essanay Movie Studio. From 1907 to 1917, Essanay was one of the premier movie companies in the country and the buildings on Vest Argyle the center of its operation. Hundreds of films were made here with actors and actresses comprising a veritable “who’s who” of early film, including Charlie Chaplin, Gloria Swanson, Ben Turpin, Wallace Beery, Beverly Bayne, Gilbert Anderson, Francis X. Bushman, and others. Film distribution and production companies plied their trade in Chicago for two decades before moving to the warmer climes of Hollywood, and although the industry moved on, the buildings on West Argyle remain as a reminder of the film industry’s vitality in Chicago.

The Beginnings of the Film Industry and Early Filmmaking Ventures in Chicago: 1896-1906

The origins of film as a popular medium date to the 1890s when Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope gained recognition and widespread distribution in amusement parlors. The Kinetoscope was essentially a peep-show viewer which projected approximately 25 seconds worth of film. The image was viewable by one person at a time through an aperture in the box containing the projector. The early projector was the culmination of various studies (including the film—and-motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge in the 1870s and the development of celluloid roll film by George Eastman the following decade) investigating the recording of moving images onto film. These concepts were incorporated into designs for a movie projector and camera by William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, an associate of Thomas Edison, and in 1891 Edison patented the camera and projector, called respectively the Kinetograph and Kinetoscope. The significance of these new devices lay more in their technical ~ aspects than their initial commercial success.

Despite the efforts expended on its development, Edison was largely indifferent to motion photography, thinking of it as a means of supplementing phonograph s recordings with pictures. He did not recognize the marketability of the Kinetoscope and thought that its commercial value was limited to its use in entertainment parlors. For that reason, he neglected to secure foreign patents on the equipment and ignored the development of a screen projection device. The vision Edison lacked, however, was more than made up by entrepreneurs in Europe and the United States. The novelty of the Kinetoscope wore away quickly, due largely to the limited range of film topics, but the Edison projector and camera were the object of refinement and improvement both here and abroad. Variations on the ya Kinetoscope and Kinetograph sprang up over the next several years, the focus of the improvements being the projection of images onto a screen viewable to large audiences. The first showings of films on a large screen occurred in 1895. Among those who saw the commercial entertainment potential of the new devices were George Spoor and William Selig, two Chicagoans whose subsequent forays into film production would, within the decade, make them two of the most influential film producers. Both men were inspired by the Kinetoscope, and working independently, they developed equipment for showing films to theater audiences.

George Spoor (1871-1953) managed a newspaper stand in the Chicago & North Western’s Wells Street Station and was a part-time manager of the Waukegan Opera House when he came upon the Kinetoscope. In the mid—1890s, Spoor collaborated with Edward Hill Amet to produce the Hagniscope projector which had its debut in 1896. Thereafter, Spoor established the National Film Renting Company through which he not only installed and operated projectors in vaudeville houses throughout the country but also distributed films. An interesting footnote from this era is Spoor’s hiring of Donald J. Bell as his chief operator in charge of projector installation and Albert S. Howell as head of maintenance. Bell and Howell eventually left Spoor to form their own film equipment manufacturing company in 1907.

From all accounts, Spoor’s local film rival, Colonel William Selig, was an eccentric and inveterate show business personality. Described by one film historian as “not a Colonel of the U.S. Army, but a tent- showman colonel.” Selig was born in Chicago in 1864 but moved west and founded a minstrel troupe in California. He returned to Chicago in the mid-1890s. Exposure to the Kinetoscope and similar devices apparently broadened Selig‘: interest in entertainment ventures, and he set up a film supply business on Peck Court. By the end of 1896, Selig was selling not only the Selig Standard Camera and the Selig Polyscope Projector but had gone a step further than Spoor by producing his own films. The careers of two other prominent film executives had their beginnings in Chicago. George Kleine was perhaps the most influential movie executive of his day for his role in attempting to mediate the patent wars that entangled filmmakers at the turn of the century. Kleine’s initial contact with the industry had been in the mid-1890s with the founding of the Kleine Optical Company, a movie and equipment supply business. He subsequently organized a large film distribution operation, and, with two other partners, founded the Kalem film studio. In 1906, Carl Laemmle, Sr., left his position with a clothing company in Oshkosh, Wisconsin to come to Chicago where he opened a nickelodeon on Milwaukee Avenue near Ashland. Six years later, he formed Universal Pictures — supposedly in Chicago, though it never operated here — and with Irving Thalberg made that company into an industry giant.

By in large, the quality of film topics for the decade beginning in 1896 did not correspond to the advances in equipment. Movies were largely adjuncts to other entertainments, sharing billings with lecturers, vaudeville performances, and “magic lantern” shows. The natural “documentary” films of the French brothers August and Louis Lumiere, as well as movies by other French filmmakers such as Georges Melies, Leon Gaumont, and the Pathe Brothers, brought about a new visual identity for cinema independent of the theatrical character that predominated in most early film productions. Unfortunately, the popularity of these films did not encourage honest artistic emulation as much as it prompted piracy and pale imitations. The films were typically one reel in length, lasting from one to ten minutes. According to William Grisham in his dissertation on film-making in Chicago, most films consisted of fragments of scenes from popular plays, condensed vaudeville and burlesque turns, scenic views, topical news items, and glimpses of celebrities. The most important American film of this period was The Great Train Robbery, made in 1903 by Edwin S. Porter of the Edison Company. The film was significant for the use of uniquely cinemagraphic devices — such as narrative crosscutting, or cutting back and forth in time and space between scenes — to convey more complicated plots.

The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company 1907-1917

The commercial success of The Great Train Robbery and the evolving sophistication of plots and cinematography began to make film a popular medium. Probably in. response to the general enthusiasm for film, George Spoor, by 1907, became interested in expanding his involvement in film from distribution to production. That year, Spoor was approached by Gilbert M. Anderson (1882-1971) who was interested in forming a film company. Anderson, who was born Max Aronson, was a vaudeville actor whose principal claim to fame had been his role as one of the four bandits in The Great Train Robbery. Following that movie, Anderson. became a producer for William Selig who, realizing the popularity of a new movie genre, the western, was filming cowboys and Indians on the prairies of’ Rogers Park. Anderson produced a few westerns in genuine western locations for Selig before talking with Spoor about a film partnership. The two had complementary abilities and experience, Spoor in the management of a national film distribution firm, and Anderson in all levels of film production. In April 1907, the two formed the Peerless Film Manufacturing Company, but by August they renamed the business the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, “ess” for Spoor and “ay” for Anderson.

Their first release, An Awful Skate, or the Hobo on Rollers, was directed by Anderson and starred Ben Turpin as an erratic roller skater careening into people on a city street. The movie, which was filmed outside of their studio at 501 North Wells Street, was an immediate success for the new company, gaining distribution throughout the country. The success of Essanay”s first comedy was appropriate for the studio that would eventually bill itself as the “Home of Comedy Hits.” Anderson stayed behind the camera in the first years of Essanay’s existence, and through his guidance the studio established a solid reputation for comedies and melodramas. As notable as any group of Essanay’s films, however, were its Broncho Billy westerns in which Anderson himself starred, making him the first moving-picture cowboy hero. In 1908, he made The Life of Jesse James, using locations in and around Chicago. The success of the movie encouraged him to organize a studio in the western United States for shooting cowboy adventures. Filming movies in Boulder and Golden, Colorado, Anderson eventually established the Essanay Western Company at Niles Canyon, California (now part of Fremont, twenty miles south of Oakland). The Niles studio was the location for the filming of many of the 376 Bronco Billy adventures that starred Anderson.

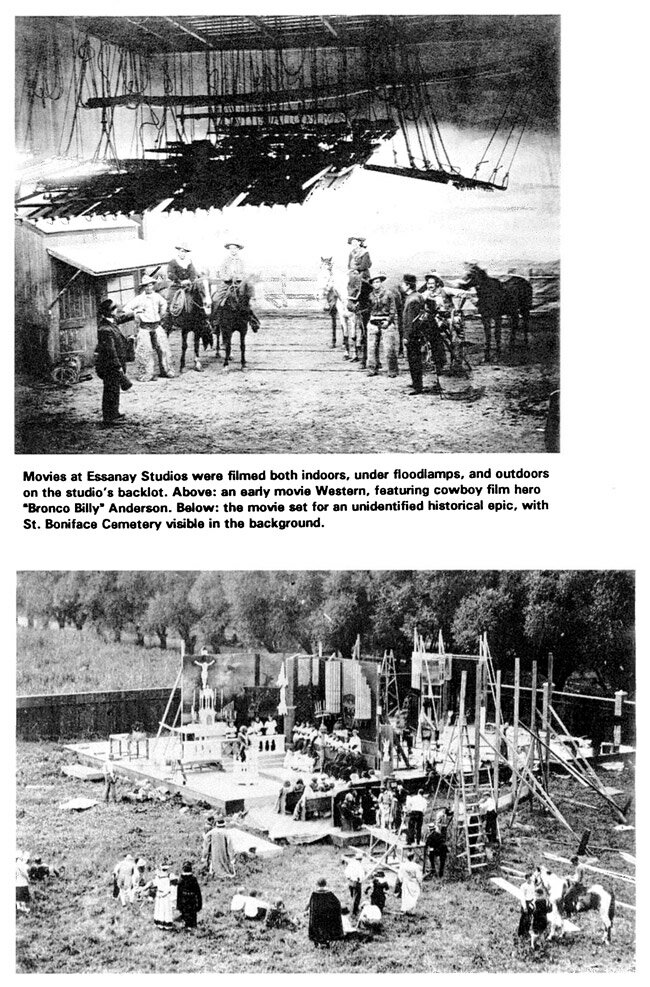

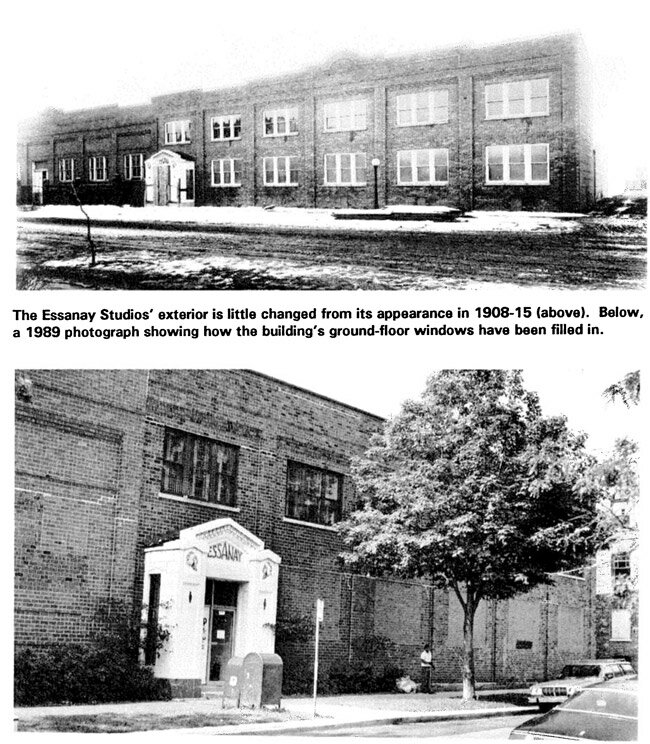

As the popularity of Essanay’s movies increased, Spoor and Anderson undertook the construction of the large Argyle Street studio. The complex is comprised of several one- and two-story, common brick buildings housing the various activities necessary for filmmaking. The street elevations of the four buildings fronting on Argyle Street conform to designs for light manufacturing and warehouse buildings of the period. Each facade is divided into six structural bays articulated by brick piers and is capped by a simple parapet with a stone coping. With the exception of the two-story westernmost building, the structures are one story in height. Construction of the first of the buildings was begun in November 1908, and the erection of the other structures occurred intermittently through 1915. The utilitarian character of the building designs is offset by the decorative entrance on the westernmost building. The doorway projects from the building and is formed of glazed white terra cotta. It has a pediment overhead with “ESSANAY” in the tympanum, and on the blocks flanking the entrance are two Indian head profiles. The Indian head, which was the Essanay trademark, was designed by Spoor’s sister when she was a student at the School of the Art Institute. Although the mark was prolific in the company’s advertising and was popular in advertising at the time, the specific reason, if there was any, for the company’s selection of this motif is unknown. Described by its house newspaper, the Essanay News, as a “veritable labyrinth of possibilities in motography production,” the complex included three large studios and space for other related operations, including a carpentry shop, prop and wardrobe storage, dressing rooms, film processing, and publicity. The studio also included one of the most sophisticated lighting systems of its time. Films were also shot outside in the court surrounded by the buildings.

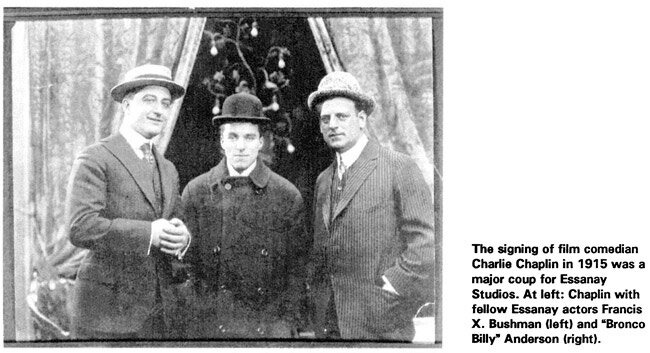

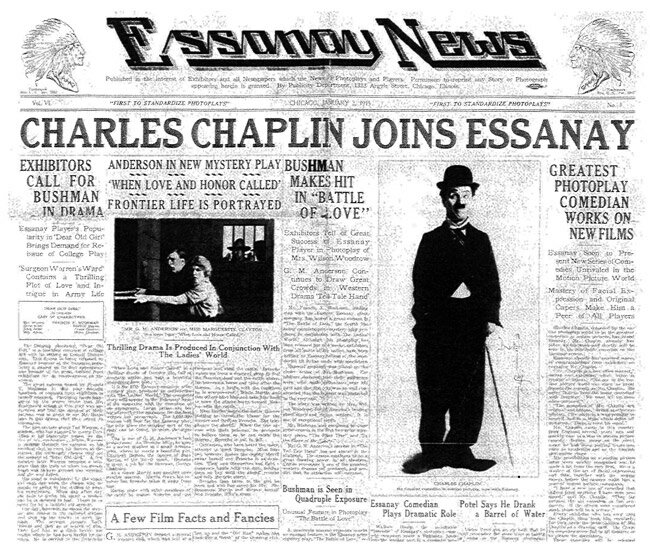

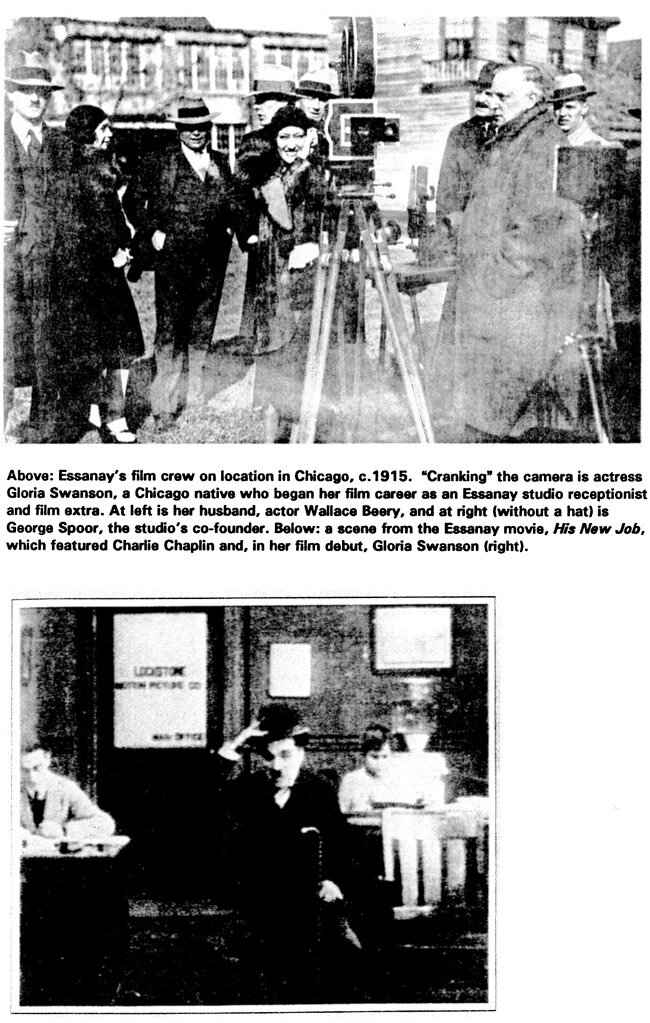

The new studios were conducive to the melodramas that took on an increasing role in, Essanay’s repertory. Whether in the context of contemporary settings or historical epics, melodramas and romances were prominent themes which also provided the vehicles to stardom for the first generation of screen stars that worked for Essanay. Francis X. Bushman began working for Essanay in 1911 and immediately became the leading male screen idol of his day. Beverly Bayne was a 16-year-old Hyde Park High School student when she first ventured onto the Essanay soundstage. Within two years, hers was one of the most recognized faces in the country. Gloria Swanson was “discovered” when she toured the studio with her aunt. In her earliest roles, Swanson worked with Katherine Anne Porter as an extra. The scripts for the movies were penned by some of the best known writers of the day, including Ring Lardner and Hobart Chatfield-Taylor, with Louella Parsons, who later became one of the leading film columnists, heading the scenario department. By far, Essanay’s biggest star was Charlie Chaplin who was signed by away from Max Sennett’s film company in December 191A through the efforts of Gilbert Anderson. Signed for the unheard-of sum of $1,250 per week, Chaplin was not particularly fond of Chicago or its climate and made only one movie, His New Job, at the Argyle Street studio. Ben Turpin, the burlesque comedian who had starred in Essanay’s first film and who in later Chaplin films served as a comic foil to Chaplin’s characters, appeared with Chaplin for the first time. Gloria Swanson, working as an Essanay extra at the time, played the receptionist. The remainder of his Essanay films were made at Essanay’s Niles Canyon studio. Chaplin remained with Essanay for only a year before signing with the Mutual Company. Chaplin’s departure marked the beginning of the end for Essanay.

Disputes between Spoor and Anderson apparently culminated with Spoor’s refusal to make a good-faith effort to sign Chaplin, and in 1915 Anderson sold his shares in the company to Spoor. The biggest problem facing Essanay was its survival in the face of losses in major courtroom battles that had been waged throughout the industry for more than a decade. In 1908, the major motion picture companies, nine in all, including Essanay and Selig in Chicago, formed the Motion Pictures Patent Company as a means of settling the patent infringement suits brought by Thomas Edison as early as 1897. The company, which included Edison, effectively monopolized film production by threatening to cancel their contract for film with George Eastman if he sold to anyone else. The same producers also formed the General Film Company to control the distribution of films. In 1915, the Supreme Court found that the companies violated the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and ordered them to disband. In the face of increased competition, and the loss of its biggest star, as well as larger industry changes (the development of the “star system” and its associated expensive contracts, and the centralization of the industry in California), Essanay closed its operation in 1917.

Ironically, the studio was sold in 1917 to Wilding Pictures, a subsidiary of Bell & Howell, the corporation founded by two of George Spoor’s former employees. In 1973, that company donated the buildings to WTTW, the local public broadcasting company affiliate. Since then the buildings have been acquired by St. Augustine College, a school serving Hispanic students. Portions of two of the buildings are occupied by the Essanay Stage and Lighting Company which, though unrelated to the original occupants, nonetheless continues to use one of the original soundstages.

APPENDIX

Criteria for Designation The following criteria, as set forth in Section 2-120-620 of the Municipal Code of the City of Chicago, were considered by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks in determining that the Essanay Studios should be recommended for landmark designation.

CRITERION 1 lts value as an example of the architectural, cultural, economic, historic, social, or other aspect of the City of Chicago, State of Illinois, or the United States. Essanay Studios was one of the most important movie-making companies in the world from 1907 to 1917. ln its ten years of operation, the company made significant contributions to the development of artistic and technical aspects of movies. lt transformed the perception of movies from a scientific curiosity into an immensely popular and commercially successful entertainment medium. Essanay concentrated on the production of comedies and melodramas that were based on real-life circumstances. ln doing so, they departed from the standard movie themes of the day, such as travelogues and historical subjects. Essanay also introduced the concept of “movie stars,” heavily promoting their actors and making them into national celebrities. Through its innovations, Essanay Studios enhanced the popularity of the young movie-making business.

CRITERION 3 Its identification with a person or persons who significantly contributed to the architectural, cultural, economic, historic, social, or other aspect of the development of the City of Chicago, State of Illinois, or the Untied States. Essanay Studios was founded in 1907 by George Spoor and Gilbert Anderson, two important movie-making pioneers. (The Essanay name was formed from the combination of Spoor and Anderson’s initials: S 81 A). Spoor was the company’s business agent, recognized for his marketing skills and his involvement with the creation of early cameras, projectors, and related technical innovations. Anderson was in charge of artistic development. Born Max Aronson, he was better known as “Bronco Billy“ Anderson, the first movie cowboy idol. Anderson inaugurated the Broncho Billy role at Essanay, and made almost 400 films in this series throughout his career.

More than any other aspect of its significance, however, Essanay is most popularly remembered for the movie stars it produced. Essanay’s biggest coup was ‘ signing Charlie Chaplin in 1914. Although Chaplin made only one movie (His New Job) at the Argyle Street studios, he made many others at Essanay’s California studio, near Oakland. Chaplin’s work at Essanay, along with that of comic actors Ben Turpin and Max Linder, established the company’s reputation as the “Home of Comedy Hits.” Essanay’s melodramas and romances were the vehicles to stardom for the industry’s first generation of actors and actresses. Gloria Swanson was “discovered” while she was touring the studio with her aunt. In her earliest pictures, she played small rolls with the writer Katherine Anne Porter. Another actress, Beverly Bayne, was a 16-year-old Hyde Park High School student when she made her first Essanay film; within two years, her face was one of the most recognized in the country. Two prominent leading men, Wallace Beery and Francis X. Bushman, also began their careers with Essanay.

CRITERION 4 Its exemplification of an architectural type or style distinguished by innovation, rarity, uniqueness, or overall quality of design, details, materials, or craftsmanship. The Essanay buildings themselves are vital to relating the story of early feature-film production. The company began construction of its Argyle Street buildings in 1908, and continued to expand the complex through 1915. George Spoor had a keen interest in technical aspects of film and developed what was recognized as a state-of-the—art filmmaking facility. The structures housed three large studios and space for related operations: carpentry shop, prop and wardrobe storage, dressing rooms, film processing and storage vaults, and administrative and publicity offices. The quality of the building’s layout is reinforced by the fact that the buildings were used continuously, by other companies, for filmmaking through the mid-1970s.

Selected Bibliography

Duis, Perry. Chicago: Creating New Traditions. Chicago Historical Society, 1976. Grisham, William Franklin. Modes, Movies, and Magnates: Early Fi/mmaking in Chicago. PhD. thesis, Northwestern University, 1982. Jahant, Charles A. “Chicago: Center of the Silent Film Industry,” Chicago History magazine. Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring-Summer 1974). Ramsaye, Terry. A Mi/lion and One Nights. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1926. Scheetz, George A. The Chicago Film Industry: Beginnings to 1978. Undergraduate thesis, University of Illinois-Urbana, 1974. ———. “Those Marvelous Men and their Movie Machines.” Chicago Tribune Magazine, Dec. 7, 1969. Additional research material, which was used in the preparation of this report, is on file at the offices of the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, Landmarks Division.

Acknowledgments

7 crrv or CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT N J. F. Boyle, Jr., Commissioner Charles Thurow, Deputy Commissioner Staff: Timothy Barton, research and writing Dwight Martin, production James Peters, layout Illustrations: Cover: from The Films of Charlie Chaplin inside front cover: from A Half Century of Chicago Building Opposite p. 1 (top). p. 5 (bot.): Department of Planning and Development Opposite p. 1 (bot.). p. 3 (bot.), P. 4 (top). p. 5 (top): Chicago Historical Society Opposite p. 2 (top). p. 3, p. 4 (bot.), inside back cover (top): from Chicago: Creating New Traditions lnside back cover (bot.): from Swanson on Swanson This report was originally prepared in 1989. It was revised and reprinted in March 1996.

COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS

Peter C. B. Bynoe, Chairman

Joseph A. Gonzalez, Vice Chairman

Albert M. Friedmin, Secretary

John W. Baird

J. F. Boyle, Jr.

Kein L. Burton

Marian Despres

Larry Parkman

Seymour Persky